Why "depowering" scrums would make rugby WORSE, not better.

The serious knock-on effects of reducing the stakes of scrums.

The background:

Rugby Union is a sport that accommodates players of all shapes and sizes, as it often pits 140kg giants against 75kg scrumhalves. This diversity is a result of the various set-piece elements that define the game, with scrums and lineouts playing crucial roles in each contest.

In rugby, the average lock stands at an imposing 6'6" (1.99m) tall—a size predominantly required for lineouts. On the other hand, props tend to be shorter but are generally the heaviest players on the field, as they must engage in scrum contests demanding exceptional upper-body strength.

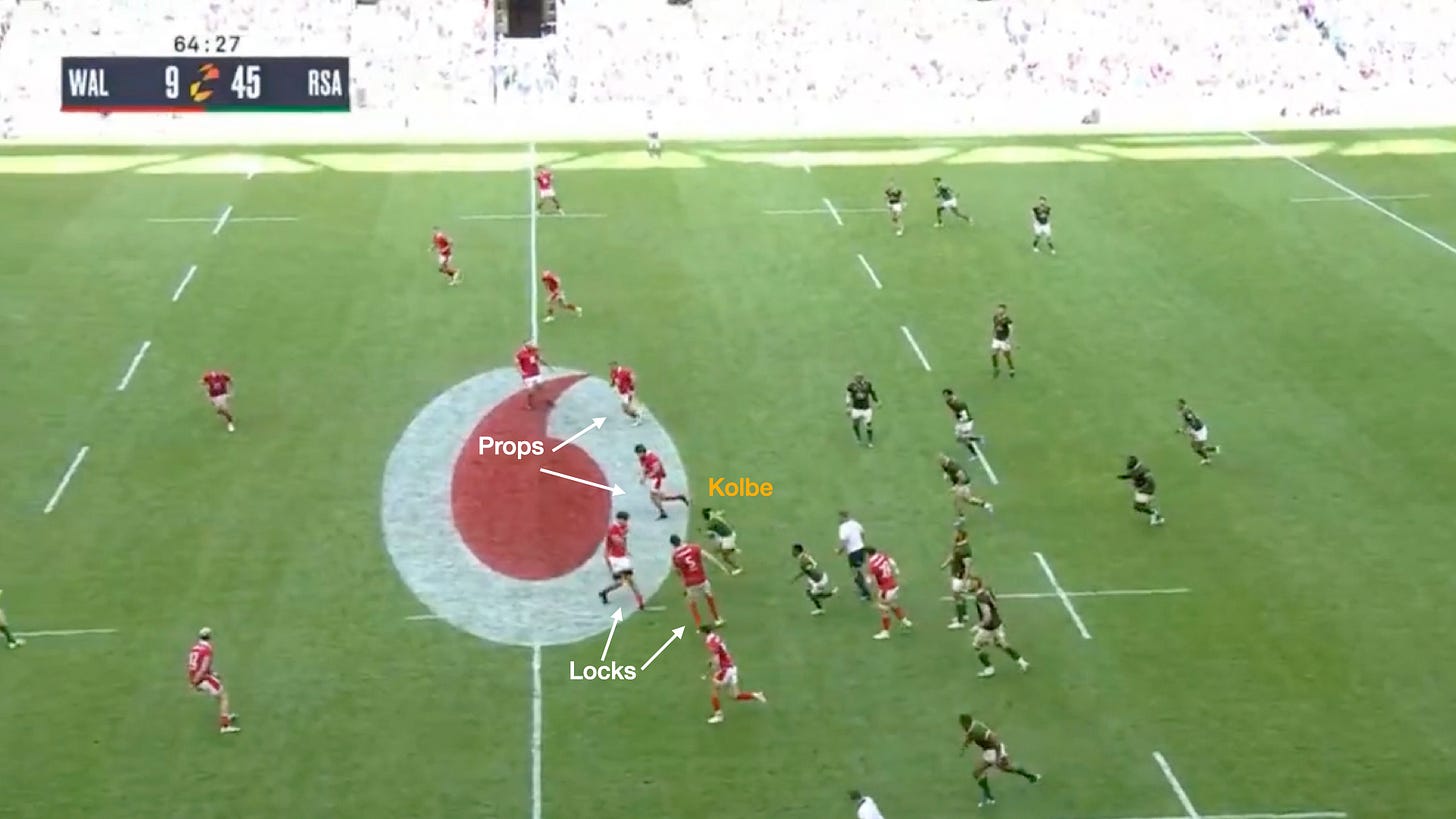

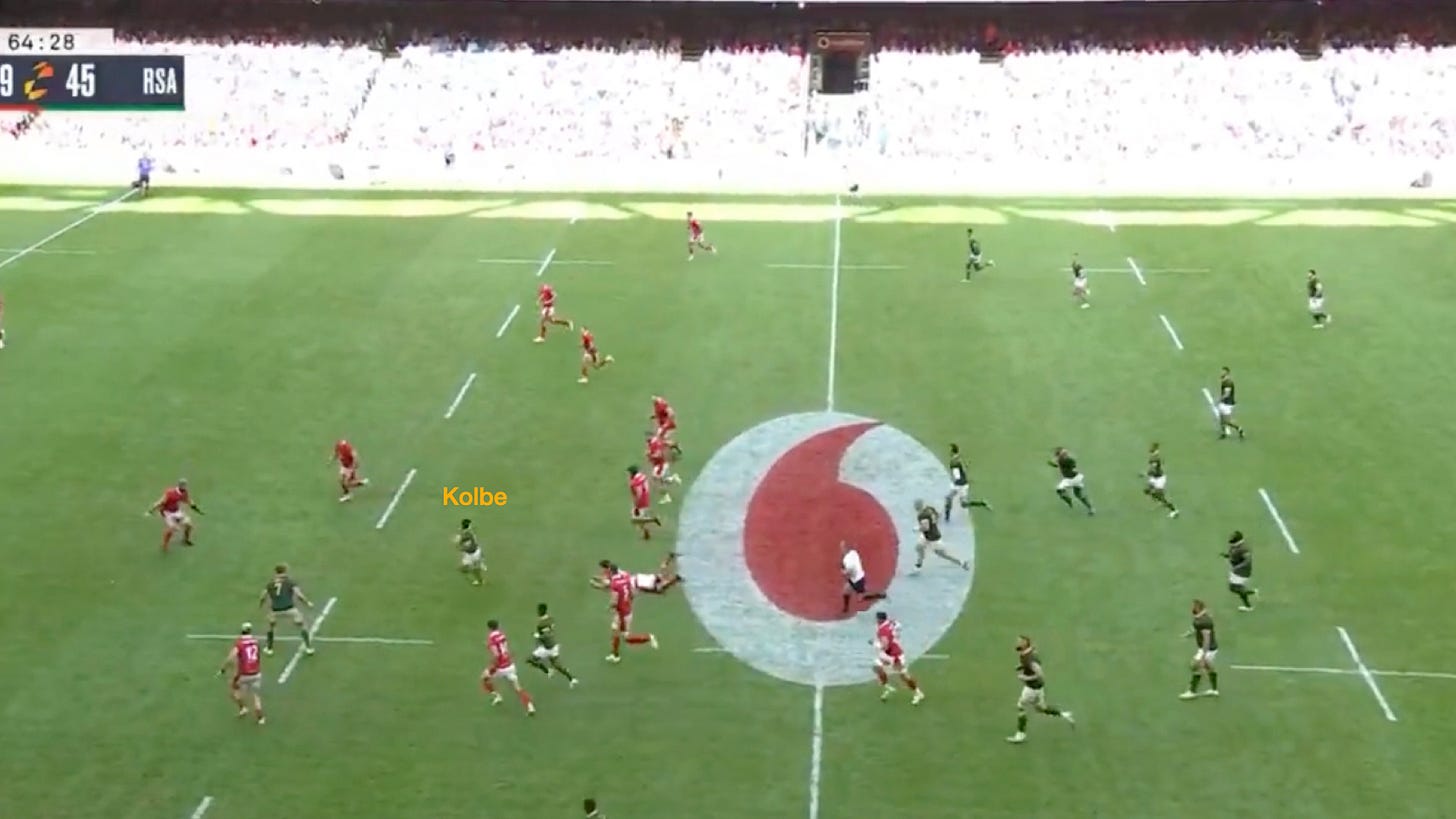

However, with defensive systems continually evolving, the vulnerabilities tend to be these less mobile set-piece specialists who lack the agility of their loose-forward and backline counterparts. This weakness is frequently exploited during kick counter-attacks when a fullback or winger runs the ball or in general open play situations.

The issue:

If scrum infringements were no longer punishable offences, the need for the larger, more scrum-focused props would depreciate.

By depowering the scrum and effectively diminishing its importance, you would reduce the need for a group of players who contribute some of the game's most prominent personalities. No longer would we have the likes of the cake-loving Ox Nche or the charismatic Joe Marler; instead, we'd see fitter and more mobile players resembling loose-forwards rather than traditional props. Consequently, this change would result in fewer opportunities for linebreaks, as teams would be able to close down spaces more rapidly, leaving fewer gaps in the defensive line.

In the 2023 RWC, before the semi-finals, the average amount of scrum penalties conceded per team was 2.15 for the entire tournament. Hardly justification for reducing their importance in favour of less space for attacking players.

Additionally, this shift would pose a risk to these 'new generation' props. Scrums would still demand extreme weight-bearing from the front row, even with reduced significance. Consequently, these leaner, more mobile props would continue to face the physically demanding stress levels of scrummaging, but with body frames less suited to the task.

Conclusion:

The scrum serves as a vital element in rugby, offering purpose even to that 45-year-old amateur club rugby player who walks around the pitch, eagerly anticipating their chance to scrum. It's the reason why tighthead props are among the highest-paid players in professional rugby, despite often lacking the speed, agility, or ball skills of many of their counterparts.

Consider, for a moment, how much more exciting football (soccer) would become if a handful of outfield players were +130kgs, akin to the likes of Frans Malherbe or Uini Atonio in rugby. The additional space and opportunities they'd introduce could be game-changing, leading to a surge in goals scored.

Rugby is certainly not football, but removing the importance of scrums would not only make rugby matches less entertaining but also erase an art form that has long captivated and provided employment. Furthermore, it would risk driving players with the traditional scrummaging physique towards extinction.

If the goal is to witness more tries in rugby, the scrum must remain protected and integral to the sport.